California’s high-speed rail project has reached a critical crossroads. Federal authorities have threatened to pull roughly $4 billion in grants, casting doubt on the future of the Central Valley leg and the broader LA–SF vision. A June 4 letter from the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) to the California High-Speed Rail Authority gave the agency just over a month to address serious criticisms of project management outlined in a 300-page compliance review. Among the key concerns: the FRA says there is “no credible plan” to close a multi-billion-dollar funding gap, citing what it called a “pattern of broken promises” since the project’s inception.

A visual rendering of the planned California High-Speed Rail project. Image courtesy of the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

California voters approved Proposition 1A in 2008, authorizing nearly $10 billion in state bonds to launch the rail effort. The state has also relied on cap‑and‑trade revenue: about 25% of those auction proceeds, now returning roughly $750 million to $1.25 billion yearly, have gone toward the rail project. With the Federal Railroad Administration pulling back, Governor Newsom’s budget proposes $1 billion a year forward from cap-and-trade funds. While state revenue covers most of the budget to date, uncertainty looms if cap-and-trade auctions slow or expire in 2030.

The FRA pointed to findings from a February report by California’s Office of the Inspector General, which identified a $6.5 billion shortfall for the initial 171-mile segment between Bakersfield and Merced.

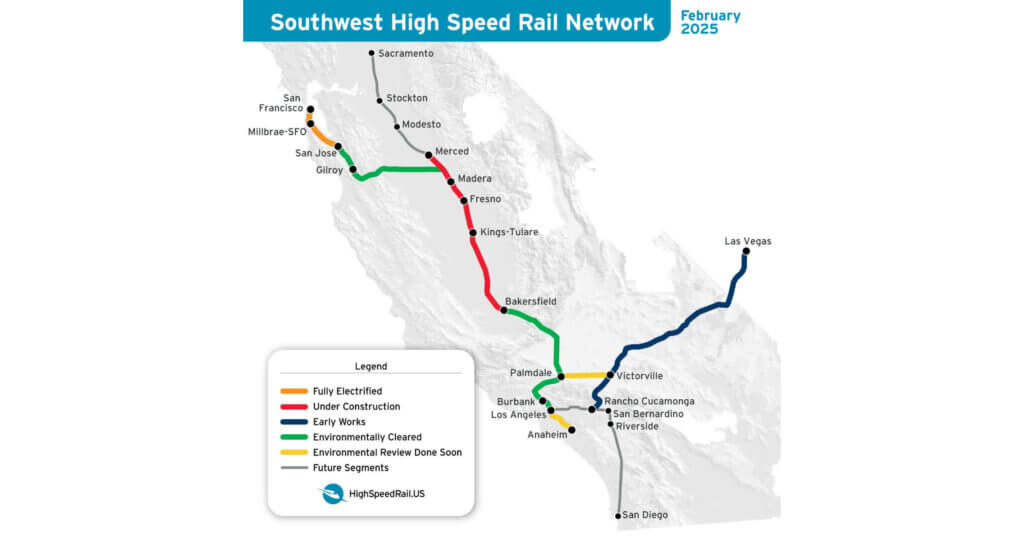

California High-Speed Rail route map. Image courtesy of the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

That report also warned it is “increasingly unlikely” the segment will be finished by its 2033 target date. Originally envisioned as an 800-mile network connecting San Francisco and Southern California by 2030, the project now aims to begin service on the Merced-Bakersfield line between 2030 and 2033 at a cost of up to $35 billion.

With federal funding in jeopardy, the project’s financial survival depends on the strength of state-backed revenue and creative financing via bonds, cap‑and‑trade proceeds, and private investment. California voters approved Proposition 1A in 2008, authorizing nearly $10 billion in state bonds to launch the effort. The state has also relied on cap‑and‑trade revenue, with about 25% of auction proceeds—roughly $750 million to $1.25 billion annually—supporting the project. Governor Newsom’s proposed budget includes $1 billion a year in cap-and-trade funding moving forward.

Still, there’s risk: cap-and-trade auctions could slow or expire by 2030, leaving future funding uncertain.

Private financing could help fill the gap, but many doubt investors will back a costly public project facing repeated delays and rising budgets. The FRA has made clear it sees no viable path forward without federal dollars, and outside observers warn that political will to replace that funding with state dollars alone is limited.

Despite these challenges, the rail authority defends the progress of the California high-speed rail project.

A spokesperson said the FRA’s conclusions don’t reflect the significant work completed so far, and emphasized the state’s commitment to delivering the nation’s first true high-speed rail system. The authority has resolved lawsuits in the Bay Area, construction continues on Central Valley tracks, and Governor Newsom remains supportive.

The California high-speed rail project retains some momentum, but its future rests on securing steady dollars and delivering on promises that have been delayed for over a decade.

Want more straight talk on public infrastructure, construction contracts, and labor impact? Sign up for the Under the Hard Hat newsletter at https://underthehardhat.org/join-us/ to stay informed and jobsite-ready.